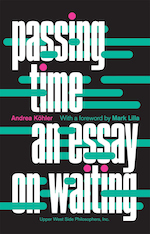

(Subway Line, No. 11)

(With a Foreword by Mark Lilla)

(February 2017)

“... a book dripping with wisdom. Köhler has an exquisite feeling for the tempo and the temporality that is required for a decent and beautiful life ...”

—LEON WIESELTIER

“Apart from being clear-eyed and utterly original, Passing Time is also irresistible. It manages to make you think that you're as smart as it is. I read it twice just to treat myself.”

—RICHARD FORD

“This is one of the most thoughtful, insightful, and enchanting books I have read in a long while. Köhler draws on personal experience as well as the testaments of literature and philosophy to show how waiting, in its various modalities, lies at the heart of the human condition. A book to be reread many times.”

—ROBERT POGUE HARRISON

Available as an eBook at Smashwords, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Kobo, Apple, Blio, and other fine eBook retailers.

ISBN 978-1-935830-48-1 (print)

ISBN 978-1-935830-49-8 (ebook)

Graced with lyricism, Passing Time is a thoughtful and wide-ranging meditation on the ways in which human beings are compelled — and choose — to mark time, from earliest childhood to the final moments of life. This is an unsparing, yet often poetic, essay on the ordeals and pleasures inherent in the universal experience of waiting.

“A philosophical masterwork on time, transitions, patience, and the end-game of death.”

“In these meditations, Swiss journalist Köhler argues that in an era where time is shaped by technology (the instantaneity of e-mail, the delays imposed by customer service ‘please wait’ messages), ‘the art of waiting needs to be learned.’ Her book is modest in size but abundant in content, and allusive but fully accessible. It insists on ‘the joyful aspects of waiting, slowness, and rest.’ Köhler shares a relaxed, cosmopolitan erudition with the reader. A veritable pantheon of distinguished writers accompany her reflections, among them Samuel Beckett, Dante, Homer, and Marcel Proust. What waiting means, as it occurs at different times and in different places, is the governing question. Köhler observes waiting in the train station, in the doctor’s office, and in bureaucratic agencies. Going from the waiting of children for celebrations to the waiting of condemned prisoners for execution, she conveys a sense of both the gift and the anxiety of time. Along the way are enriching tidbits: an etymological digression into the word ‘wait’ itself, a historical reminder of the appearance of a railroad timetable. What haunts this lively challenge to the passage of time is the ‘paradox of an overabundance of too little time’ in contemporary life.”

“What are we doing when we aren’t doing anything? We’re waiting. Or, as Köhler would prefer, we’re passing time. As Mark Lilla notes in his foreword: ‘Man is the waiting animal … What exactly is it to wait?’ Köhler, the cultural correspondent for a Swiss daily newspaper and winner of the 2003 Berlin Book Critics Prize, posits, ‘waiting is a state in which time holds its breath in order to remind us of our mortality. Its motto is not carpe diem but memento mori.’ Now available in English, her extended essay is a hybrid: part meditation, part philosophy, part autobiographical musings. One comment about waiting leads to another, which leads to some author’s comment on the first comment, which leads to another comment. The book reads like a string of epigrammatic musings. Köhler goes on to describe all manners of waiting and their significance, creating a sort of taxonomy of waiting. There’s anxiety, hesitation, expectation, laggardness, etc. She draws on a wide variety of writers, mostly European, to help her along the way: Barthes, Benjamin, Foucault, Camus, Blanchot, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Peter Handke, the self-proclaimed ‘lover of waiting.’ Köhler describes him as ‘one of the staunchest defenders of slowness in our time.' As she sees it, waiting is a good thing. It’s not a waste of time but rather a use of time. She also references Richard Linklater’s film Before Sunrise and its sequel, Before Sunset, both of which address an ages-old question: is there someone out there, waiting for me? Of course, Waiting for Godot makes an appearance. Poor Vladimir and Estragon ‘practice waiting for its own sake and with no particular goal in mind.’ We wait with them, confronting matters of existence and eschatology while time is passing. As Vladimir says, ‘it would have passed in any case.’ A lovely jeu d’esprit for those waiters who like their abeyance with a touch of the metaphysical”

“The way we live now is by making war on human — and humane — time. Historians will record that we were complicit in the dictatorship of speed and the repudiation of patience. But not all of us; and certainly not Andrea Köhler, who has written a book dripping with wisdom. Köhler has an exquisite feeling for the tempo and the temporality that is required for a decent and beautiful life. There are deep and true observations on every page. Passing Time is a gift to the resistance.”

“Apart from being clear-eyed and utterly original, Passing Time is also irresistible. It manages to make you think that you're as smart as it is. I read it twice just to treat myself.”

“This is one of the most thoughtful, insightful, and enchanting books I have read in a long while. Köhler draws on personal experience as well as the testaments of literature and philosophy to show how waiting, in its various modalities, lies at the heart of the human condition. A book to be reread many times.”

“All the excitements and longueurs of anticipation are fully satisfied in this gem of a book. Andrea Köhler’s beautiful and profound reflections on life’s interstitial spaces—the queue, the waiting room, the place held for two when only one has arrived—at once poetic and philosophical, intimate and analytical, form the perfect antidote to the headlong rush of our culture. I picked this slim volume up in a bookstore and didn't leave until I had almost finished it. It is one of those rare books that, like Rilke’s ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’, makes you feel that you must change your life, or perhaps more urgently, the way you think about your life. Truant time is rescued and restored here, and nothing could waste it less than to read this lovely book.”

“... there might be more living done in our in between moments than in those we have big names for. Waiting in line, hoping you’ll get a ticket; waiting for someone to call; waiting to find the courage to make the call; waiting to hear results. We live in abeyance. What a beautiful book.”

“Graced with lyricism, Passing Time is an engaging meditation on the ways in which human beings are forced — and choose — to mark time, from earliest childhood to the final moments of life. This is an unsparing, yet often poetic, essay on the ordeals and pleasures inherent in the universal experience of waiting.”

“... a book of great intelligence and rare beauty ...”

With a Foreword by Mark Lilla

Translated by Michael Eskin

ISBN 978-1-935830-48-1 (print)

ISBN 978-1-935830-49-8 (ebook)

Publication Date: February 25, 2017

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andrea Köhler is a cultural correspondent for the Swiss daily newspaper Neue Züricher Zeitung and the recipient of the 2003 Berlin Book Critics Prize. Aside from the The Waiting Game: An Essay on the Gift of Time, she has also published (together with Rainer Moritz) Kleines Glossar des Verschwindens (2003) and Maulhelden und Königskinder (1998). She currently lives in New York City.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM PASSING TIME

Waiting is an imposition. Yet only waiting in its manifold guises — in traffic or love, at the gate or the doctor’s — affords us an embodied sense of time and its promises. We wait: for spring and the jackpot, for the food, for an offer, for the one, and Godot — for test results, happiness, birthdays, and laughs — for a call, for what’s next, for the knock on the door — for the pain to subside and the storm to blow over ... Idleness, byways, detours, and boredom — waiting is the page in the book of planned hours that needs to be filled. With luck, its reward will be freedom.

I love the transitions, the liminal states, the hours undefined — for a while, anyway — the twilight that heralds the night, which, in turn, promises more than just morning’s return. Those who can wait know well what it means to live in the conditional tense. However, if fooled by false hopes we don’t make our choices, insisting on ‘keeping our options open’, we’ll easily miss opportunity’s call and let life pass us by. Such sins of omission are the stuff of literature, which is ruled by an economy of attention whose costs and benefits cannot be gauged by the standards of our fast-paced, over-committed everyday lives, and which enjoins us — as already Seneca surmised — to spend our time in meaningful and hopefully also fulfilling ways.

There is no growth, no development without waiting — think of pregnancy, puberty, or the strains of creative labor. Maybe that’s what Franz Kafka meant when he referred to his own life as a “hesitation before birth.” Waiting means imagining what might or might not happen. Moreover, insofar as it implies keeping desire in check it lies, as Sigmund Freud has suggested, at the root of all symbolic communion and can thus be considered humanity’s first major cultural achievement.

If we think of life as an irregular concatenation of instants, including those moments when the steady flow of expectation is suddenly interrupted and we feel stuck, then these temporary breaks will appear above all as congestions or interferences in the world of chronic simultaneity we have created at the expense of the open-ended, undulating rhythms of time unfolding. Still, within the high-speed worlds of affluent societies, oases of slowness have emerged — from memorial sites to spas — designed to restore a different measure of time to the ‘hurtling standstill’ of our age. Most of these ‘islands of rest’, however, have something artificial about them, for there is no way back to paradise, which, all promises of salvation notwithstanding, was never to be had in this life anyway. Even a trip around the world will neither relieve us of time’s pressures nor lead us to heaven’s gate, as Heinrich von Kleist imagined. At best, we may wind up on a tropical island that vaguely resembles our idea of earthly bliss. Life’s most mysterious ‘island of rest’, its most enigmatic break, is undoubtedly sleep — our nightly exercise in waiting, from which we will one day no longer awaken.

We can never shake the constitutive duality of our existence, indelibly marked as it is by the unremitting interplay between sleeping and waking, absence and presence, the not-yet and the no-longer. Music may have given the most palpable expression to this duality, even though its rhythms, rests, and repetitions follow patterns that are more predictable than life’s vagaries.

I have tried to echo the rhythms of expectation and waiting by punctuating my philosophical reflections with fictional interludes spoken by an ‘I’ not unlike the author’s, who, I must confess, considers herself a member of that ‘laggard species’ that is all too often guilty of tardiness. Which is to say: I wrote this book without the slightest sense of nostalgia or cultural lament and with the sole purpose of bringing out the joyful aspects of waiting, slowness, and rest.

Of the promise of salvation, the coming of the messiah, and the utopian dream of paradise on earth I will treat only marginally — these forms of expectation involve general questions of faith any speculation on which will most likely be a foregone conclusion to the true believer. What I am interested in is the kind of waiting that falls squarely within the realm of individual experience, which, in today’s world, faces the paradox of an overabundance of too little time.

Homo sapiens is the waiting animal capable of anticipating death. Even as unpredictability is gradually eliminated from our lives (or so it seems) due to ever-shortening wait times and the vanishing of in-between spaces, our parting rituals, too — from the simple ‘so long’ to the performance of last rites — adapt to the pressures of a restless world. There was a time when each parting contained a ‘small death’, in the sense of a strong chance of never seeing each other again or losing touch for good. But since technology has made it possible to stay connected at all times, we can barely imagine what it might mean no longer to be around one day. Waiting is a state in which time holds its breath in order to remind us of our mortality. Its motto is not carpe diem but memento mori.

© 2017 Upper West Side Philosophers, Inc.

PASSING TIME — Andrea Köhler in Conversation

UWSP: What inspired you to write Passing Time?

AK: I am not a very patient person, and most of the time I hate waiting as much as anybody else. But there are also a lot of lessons in waiting. Depending on our mood or our situation, we experience time—and, for that matter, waiting—very differently. Waiting is often painful or annoying—think of waiting for a medical diagnosis—but it can also be full of expectation and hope. There is no growth, no development without waiting, nor are there rewards without a certain delay. Immediate gratification leaves us unsatisfied in the end. Achievement is always a labor of time.

I wanted to bring awareness to how important these periods of apparently useless or wasted time can be—in fact, in retrospect they often turn out to be crucial. Even inspiration needs time to emerge. Kafka called this ‘a hesitation before birth.’ And yet, waiting is also about seizing the right moment and not letting opportunity pass us by.

And then there are those wonderful moments while we wait—unforeseen moments—when we suddenly find we have ‘superfluous’ time on our hands, free to fill with whatever we please. In a way, that’s the essence of freedom: time for the unexpected, for bliss or beauty or just idleness. In short: time as a gift.

UWSP: How did Passing Time come about? And is it in any way autobiographical?

AK: The book is autobiographical only insofar as the perception of waiting is, of course, tinted by my own experiences. I didn’t write a theoretical book about time—or the lack of it—but a personal meditation on the many ways we experience time during periods of waiting.

I also included fictional ‘interludes’ to further illustrate the feelings that accompany periods of waiting—feelings like anxiety, expectation, anger, or boredom. The ‘I’ speaking in these interludes is not identical with the author; it is, rather, an investigator trying to get ‘into the head’ of a person who is waiting. In other words: these interludes show characters—male and female—caught up in what Roland Barthes calls ‘the drama of waiting.’

UWSP: Passing Time asks us to reflect on a range of philosophical, metaphysical, ethical and aesthetic issues. How did you go about interweaving these issues and the narrative, literary, and essayistic so as to achieve your book’s singular appeal and ‘intellectual-spiritual’ intensity?

AK: It’s difficult, if not impossible, to answer the question why you write the way you do. But as a reader and literary editor, I can at least say that for me style is not only more important than plot but, rather, it is the plot. The very way you say things reflects the way you feel about them. Maybe my experience in journalism has taught me how to interlace research and theory in a way that engages the imagination as much as reason. My goal was to put the reader in the state of mind of waiting—not only to meditate on but to actually feel the ambivalence of waiting, to feel the overwhelming anxiety we sometimes experience, as well as the power we might wield by having another person wait.

UWSP: What would you say is the main—or most important—thought or insight of Passing Time?

AK: I love the transitional states, the moments in-between, when everything seems possible—at least for a while. Waiting means living in the conditional tense. In our fast-paced, media-filled age, in which every interlude or pause is gradually eliminated from our lives and constant entertainment is keeping our minds busy, we are losing the ability to get in touch with ourselves.

Staying tuned in at all times also nurtures the illusion that it’s possible to avoid separation, to deny that life is about saying good-bye. Thus, we can barely imagine any longer that our time on earth is limited, that life is essentially a waiting for the end. This thought should actually make each minute precious to us. And yet there are many situations we want to be over, moments of boredom and hours of wasted time. I wanted to capture the on- and off-mode of our existence—the rhythms of life itself.

UWSP: What readership do you have ideally in mind for your essay?

AK: I want to inspire readers to get in touch with their own thoughts and memories about situations we often allow to pass unseen. I didn’t want to write some kind of self-help guide, a ‘How to Wait’-book, nor a scholarly piece, but a playful literary take on different insights into waiting—subjective as well as philosophical and psychological. I guess that’s what we call a ‘personal essay’.

UWSP: Do you have any favorite authors (essayists, novelists, poets), and if so, did you have any particular contemporaries or precursors at the back of your mind as you were writing Passing Time?

AK: Franz Kafka is an expert in waiting. The novel The Trial as well as his diaries and letters are about waiting. As is, of course, Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Another author who inspires my writing is Roland Barthes, whose style and sensitivity I love. I also like Walter Benjamin’s prose, as well as the books of the great German philosopher Hans Blumenberg, or the French poet Yves Bonnefoy, who has written literary prose of extraordinary subtlety. Most of these authors defy the idea of ‘genre’, but to a certain extent most are writers in the tradition of Montaigne.

© 2016 Upper West Side Philosophers, Inc.

- All Titles A-Z

- 17 Vorurteile, die wir Deutschen ...

- A Moment More Sublime: A Novel

- Become a Message: Poems

- Below Zero: A Play

- Channel Swimmer: A Novel

- Descartes’ Devil: Three Meditations

- Fatal Numbers: Why Count on Chance

- Gespräch über Deutschland. Mit zwei Essays

- Health Is in Your Hands: Jin Shin Jyutsu — Practicing the Art of Self-Healing (with 51 Flash Cards for the Hands-on Practice of Jin Shin Jyutsu)

- High on Low: Harnessing the Power of Unhappiness

- Homo Conscius: A Novel

- In Praise of Weakness

- Mortal Diamond: Poems

- November Rose: A Speech on Death

- November-Rose: Eine Rede über den Tod

- Of Parents and Children

- On Dialogic Speech

- On Language & Poetry

- Összes Versei

- Passing Time: An Essay on Waiting

- Philosophical Fragments of a Contemporary Life

- Philosophical Truffles

- Spanish Light

- The Complete Plays of Lajos Walder

- The Complete Poems of Lajos Walder

- The DNA of Prejudice: On the One and the Many

- The Impostors: A Novel

- The Man Who Couldn't Stop Thinking: A Novel

- The Spectator: A Novel

- The Square Light of the Moon

- The Vocation of Poetry

- The Wisdom of Parenthood: An Essay

- The Zucchini Conspiracy: A Novel of Alternative Facts

- Tyrtaeus: A Tragedy

- Vase of Pompeii: A Play

- What We Gain As We Grow Older: On Gelassenheit

- Yoga for the Mind: A New Ethic for Thinking and Being & Meridians of Thought