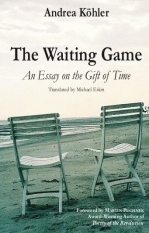

(Translated by Michael Eskin, with a Foreword by Martin Puchner)

(January 2012)

Available as an eBook at Smashwords, Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Sony, Kobo, Apple, Blio, Diesel and other fine eBook retailers.

ISBN 978-0-935830-03-0 (Softcover)

ISBN 978-1-935830-08-5 (eBook)

Graced with lyricism, The Waiting Game is an engaging meditation on the ways in which human beings are forced — and choose — to mark time, from earliest childhood to the final moments of life. This is an unsparing, yet often poetic, essay on the ordeals and pleasures inherent in the universal experience of waiting. (Jamie Venise, Ph.D.)

REVIEWS

“Graced with lyricism, The Waiting Game is an engaging meditation on the ways in which human beings are forced — and choose — to mark time, from earliest childhood to the final moments of life. This is an unsparing, yet often poetic, essay on the ordeals and pleasures inherent in the universal experience of waiting.”

“... a book of great intelligence and rare beauty ...”

Translated by Michael Eskin, with a Foreword by Martin Puchner

ISBN 978-0-935830-03-0 (Softcover)

ISBN 978-1-935830-08-5 (eBook)

Publication Date: January 2012

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Andrea Köhler is a cultural correspondent for the Swiss daily newspaper Neue Züricher Zeitung and the recipient of the 2003 Berlin Book Critics Prize. Aside from the The Waiting Game: An Essay on the Gift of Time, she has also published (together with Rainer Moritz) Kleines Glossar des Verschwindens (2003) and Maulhelden und Königskinder (1998). She currently lives in New York City.

READ AN EXCERPT FROM THE WAITING GAME

Waiting is an imposition. Yet only waiting in its manifold guises — in traffic or love, at the gate or the doctor’s — affords us an embodied sense of time and its promises. We wait: for spring and the jackpot, for the food, for an offer, for the one, and Godot — for test results, happiness, birthdays, and laughs — for a call, for what’s next, for the knock on the door — for the pain to subside and the storm to blow over ... Idleness, byways, detours, and boredom — waiting is the page in the book of planned hours that needs to be filled. With luck, its reward will be freedom.

I love the transitions, the liminal states, the hours undefined — for a while, anyway — the twilight that heralds the night, which, in turn, promises more than just morning’s return. Those who can wait know well what it means to live in the conditional tense. However, if fooled by false hopes we don’t make our choices, insisting on ‘keeping our options open’, we’ll easily miss opportunity’s call and let life pass us by. Such sins of omission are the stuff of literature, which is ruled by an economy of attention whose costs and benefits cannot be gauged by the standards of our fast-paced, over-committed everyday lives, and which enjoins us — as already Seneca surmised — to spend our time in meaningful and hopefully also fulfilling ways.

There is no growth, no development without waiting — think of pregnancy, puberty, or the strains of creative labor. Maybe that’s what Franz Kafka meant when he referred to his own life as a “hesitation before birth.” Waiting means imagining what might or might not happen. Moreover, insofar as it implies keeping desire in check it lies, as Sigmund Freud has suggested, at the root of all symbolic communion and can thus be considered humanity’s first major cultural achievement.

If we think of life as an irregular concatenation of instants, including those moments when the steady flow of expectation is suddenly interrupted and we feel stuck, then these temporary breaks will appear above all as congestions or interferences in the world of chronic simultaneity we have created at the expense of the open-ended, undulating rhythms of time unfolding. Still, within the high-speed worlds of affluent societies, oases of slowness have emerged — from memorial sites to spas — designed to restore a different measure of time to the ‘hurtling standstill’ of our age. Most of these ‘islands of rest’, however, have something artificial about them, for there is no way back to paradise, which, all promises of salvation notwithstanding, was never to be had in this life anyway. Even a trip around the world will neither relieve us of time’s pressures nor lead us to heaven’s gate, as Heinrich von Kleist imagined. At best, we may wind up on a tropical island that vaguely resembles our idea of earthly bliss. Life’s most mysterious ‘island of rest’, its most enigmatic break, is undoubtedly sleep — our nightly exercise in waiting, from which we will one day no longer awaken.

We can never shake the constitutive duality of our existence, indelibly marked as it is by the unremitting interplay between sleeping and waking, absence and presence, the not-yet and the no-longer. Music may have given the most palpable expression to this duality, even though its rhythms, rests, and repetitions follow patterns that are more predictable than life’s vagaries.

I have tried to echo the rhythms of expectation and waiting by punctuating my philosophical reflections with fictional interludes spoken by an ‘I’ not unlike the author’s, who, I must confess, considers herself a member of that ‘laggard species’ that is all too often guilty of tardiness. Which is to say: I wrote this book without the slightest sense of nostalgia or cultural lament and with the sole purpose of bringing out the joyful aspects of waiting, slowness, and rest.

Of the promise of salvation, the coming of the messiah, and the utopian dream of paradise on earth I will treat only marginally — these forms of expectation involve general questions of faith any speculation on which will most likely be a foregone conclusion to the true believer. What I am interested in is the kind of waiting that falls squarely within the realm of individual experience, which, in today’s world, faces the paradox of an overabundance of too little time.

Homo sapiens is the waiting animal capable of anticipating death. Even as unpredictability is gradually eliminated from our lives (or so it seems) due to ever-shortening wait times and the vanishing of in-between spaces, our parting rituals, too — from the simple ‘so long’ to the performance of last rites — adapt to the pressures of a restless world. There was a time when each parting contained a ‘small death’, in the sense of a strong chance of never seeing each other again or losing touch for good. But since technology has made it possible to stay connected at all times, we can barely imagine what it might mean no longer to be around one day. Waiting is a state in which time holds its breath in order to remind us of our mortality. Its motto is not carpe diem but memento mori.

© 2011 Upper West Side Philosophers, Inc.

COMING SOON!

- All Titles A-Z

- 17 Vorurteile, die wir Deutschen ...

- A Moment More Sublime: A Novel

- Become a Message: Poems

- Below Zero: A Play

- Channel Swimmer: A Novel

- Descartes’ Devil: Three Meditations

- Fatal Numbers: Why Count on Chance

- Gespräch über Deutschland. Mit zwei Essays

- Health Is in Your Hands: Jin Shin Jyutsu — Practicing the Art of Self-Healing (with 51 Flash Cards for the Hands-on Practice of Jin Shin Jyutsu)

- High on Low: Harnessing the Power of Unhappiness

- Homo Conscius: A Novel

- In Praise of Weakness

- Mortal Diamond: Poems

- November Rose: A Speech on Death

- November-Rose: Eine Rede über den Tod

- Of Parents and Children

- On Dialogic Speech

- On Language & Poetry

- Összes Versei

- Passing Time: An Essay on Waiting

- Philosophical Fragments of a Contemporary Life

- Philosophical Truffles

- Spanish Light

- The Complete Plays of Lajos Walder

- The Complete Poems of Lajos Walder

- The DNA of Prejudice: On the One and the Many

- The Impostors: A Novel

- The Man Who Couldn't Stop Thinking: A Novel

- The Spectator: A Novel

- The Square Light of the Moon

- The Vocation of Poetry

- The Wisdom of Parenthood: An Essay

- The Zucchini Conspiracy: A Novel of Alternative Facts

- Tyrtaeus: A Tragedy

- Vase of Pompeii: A Play

- What We Gain As We Grow Older: On Gelassenheit

- Yoga for the Mind: A New Ethic for Thinking and Being & Meridians of Thought